Many people with PWS have at least one orthopedic (bone/muscle) problem. A recent paper examines the how often hip dysplasia occurs in children with PWS (spoiler alert — it may happen more often than was previously thought), and offers new recommendations for screening. The study was done at the Children’s Hospital Colorado, examining the records of ninety patients seen through their PWS Multidisciplinary Clinic.

Orthopedic Problems In PWS

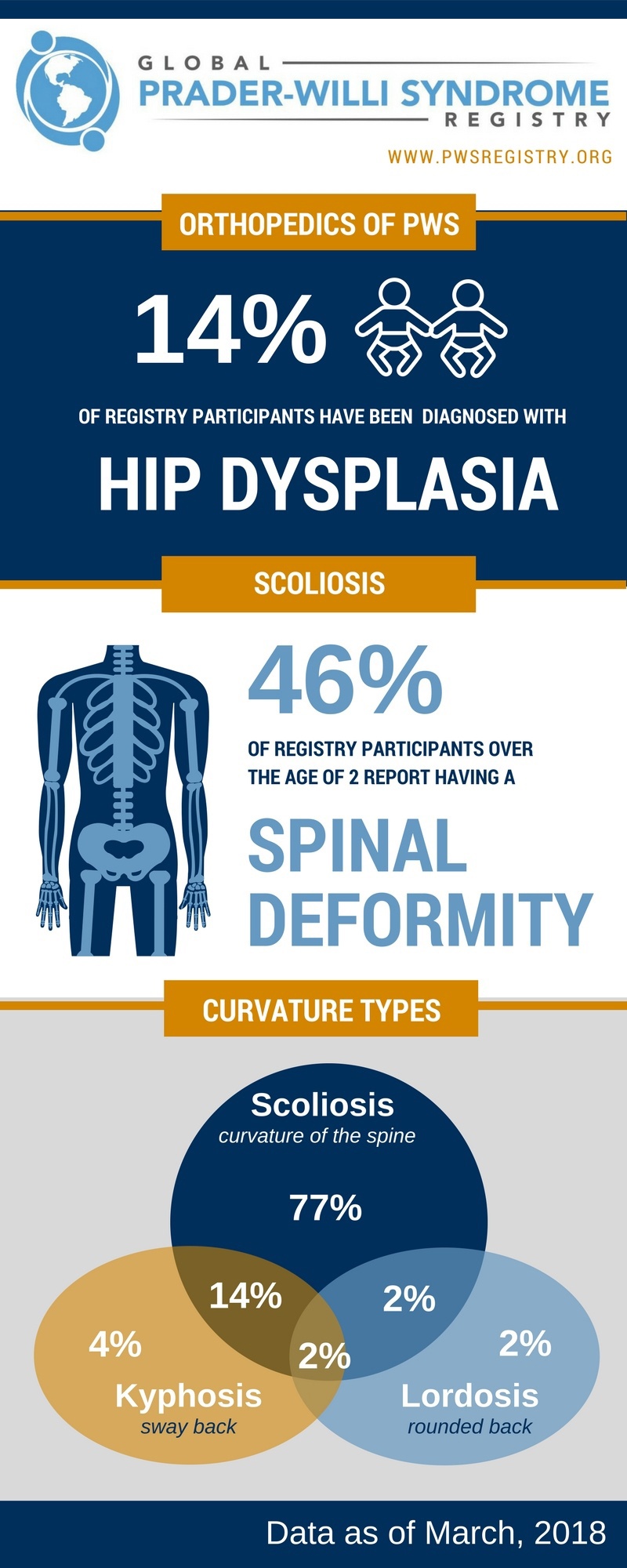

The most common orthopedic problem in PWS is scoliosis, or curvature of the spine, reported in anywhere from 15-86% of patients in the medical literature, depending on the study. In the Global PWS Registry, 46% of participants age 2 and older report a spinal deformity, such as scoliosis, kyphosis (rounded/hunch back), or lordosis (sway back). Additional skeletal problems including ‘knock knees’, ‘bow legs’ and hip dysplasia occur at higher frequency in the PWS population compared to the typical population.

The implication of these skeletal problems can range from mainly cosmetic to having serious impacts on quality of life, and thus there is the need for careful monitoring and management of bone issues throughout life.A recent paper examines the how often hip dysplasia occurs in children with PWS (*spoiler alert - it may happen more often than has previously thought), and offers new recommendations for screening.

Hip Dysplasia In PWS: New Findings

Hip dysplasia occurs when the hip socket doesn't fully cover the ball portion of the upper thighbone. This allows the hip joint to become partially or completely dislocated. Early diagnosis and treatment of hip dysplasia improves outcomes, whereas untreated hip dysplasia can lead to damage of the cartilage that lines the hip joint, and may eventually cause painful arthritis in the hip.

Treatment varies according to age at diagnosis, the severity of dysplasia, and the circumstances (eg, developmental age). Sometimes, hip dysplasia will improve with limited intervention. Often in young babies, a soft brace can be used to hold the ball of the joint in the socket for a few months to help mold it into the proper shape. In rare cases, particularly if the individual is diagnosed later, a full body cast or hip surgery may be necessary to move the bones into the proper positions for smooth joint movement.

In the current study, the authors looked at the medical records of their PWS patient for evidence of hip dysplasia, using X-ray films and ultrasound results from previous exams. Not all of the patients attending the clinic had hip films/ultrasound results (90 of 127 patients total had this information in their medical records) so the findings may over-represent hip dysplasia rates, but the authors determined that 27 out of the 90 patients evaluated (30%) had hip dysplasia. Of those 30%, the majority had hip disyplasia in both hips. This number is higher than what has been previously reported in the medical literature (6-22%), and is higher than what is currently reported in the Global Registry (14%), suggesting that hip dysplasia might be under-diagnosed in the larger PWS population. Alternatively, the retrospective nature of the study (looking back at a population after noticing a lot of hip dysplasia cases) may have skewed the numbers slightly higher.

In looking more closely at features of the patients who had hip dysplasia, there did not seem to be any particular characteristics (sex of patient, deletion vs. UPD genetic subtype, growth hormone therapy) that strongly distinguished those who had hip dysplasia from those who did not.

Since this was a study at a single medical center, similar studies at other institutions will be helpful in understanding if hip dysplasia is more common than previously appreciated. However, its clear that the incidence of hip dysplasia in PWS is much higher than in the typical population, where it occurs in ~0.1% of individuals. Since early detection and treatment with a soft brace can improve the problem in many cases, all babies with PWS should be carefully examined for signs of hip dysplasia. If hip dysplasia is found, it's important to work with an orthopedic doctor who is experienced in treating PWS, since the consequences of hip dysplasia in PWS may differ than that in the general population. The authors of this study suggest that all babies with PWS be screened by ultrasound for evidence of hip dysplasia at ~ 6 weeks of age. Since it’s not yet clear if babies who have no sign of hip dysplasia early in life might go on to develop it later, the authors also suggest children with PWS be evaluated again for hip dysplasia at age 1, 2, 5 10 and 15 years old. A separate, FPWR-funded study is currently examining the long term consequences of hip and knee problems in PWS, and should help doctors develop best practices for PWS, so that these issues can be effectively monitored or treated, without subjecting individuals with PWS to unnecessary surgery.

By participating in the Global PWS Registry, the PWS community can continue to strengthen the data so that we can better understand the incidence, severity, risk factors and outcomes for orthopedic problems in PWS. If you have not completed your orthopedic survey, please do so, and please update your record with any changes so that we can share the most up to date information back to you and the entire PWS community.